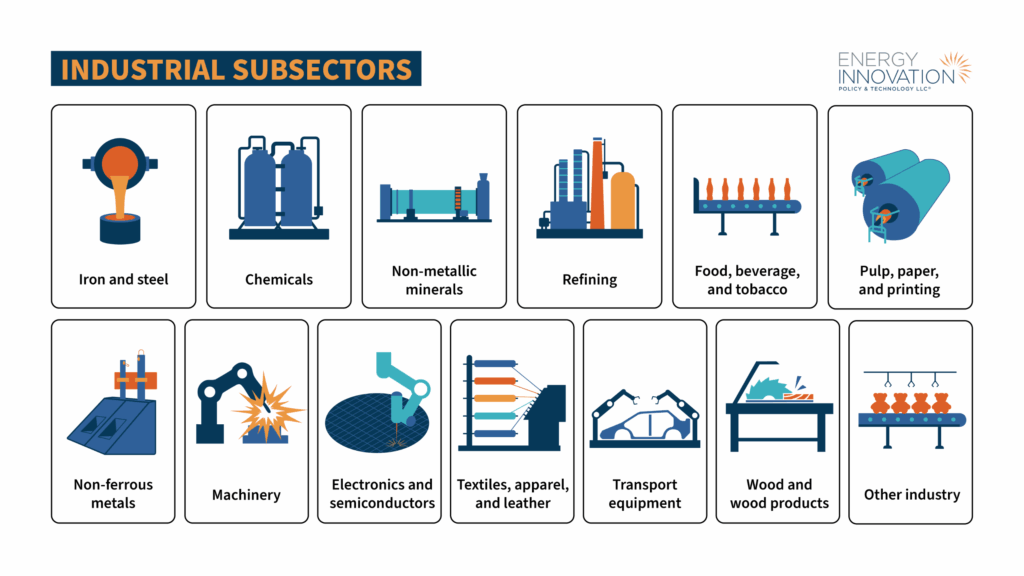

The industrial sector makes the products and materials we rely on every day – from the steel in our vehicles to the concrete in our buildings to the clothes we wear.

Each industrial subsector consumes different amounts and types of energy.

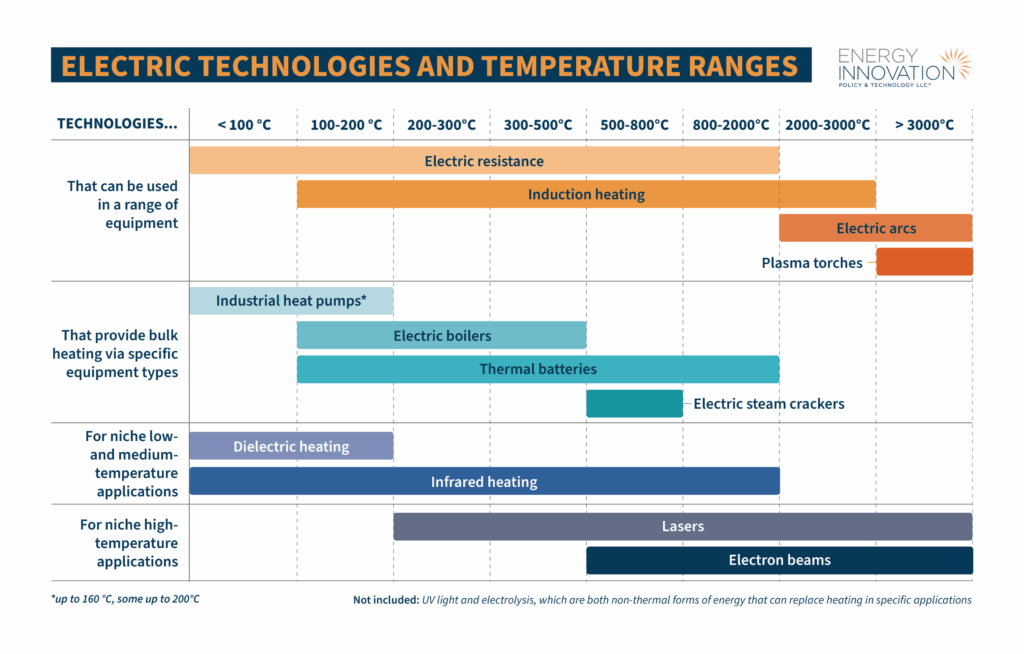

Heating for industrial processes (such as melting metals or cooking food) accounts for 84 percent of industrial non-feedstock fossil fuel use, with about a third of that demand falling into a low-temperature heat range (below 200°C). High-temperature process heat (over 500°C, but seldom more than 1,800°C) is concentrated within a handful of industries, namely iron and steel, non-metallic minerals, chemicals, refining, and non-ferrous metals.

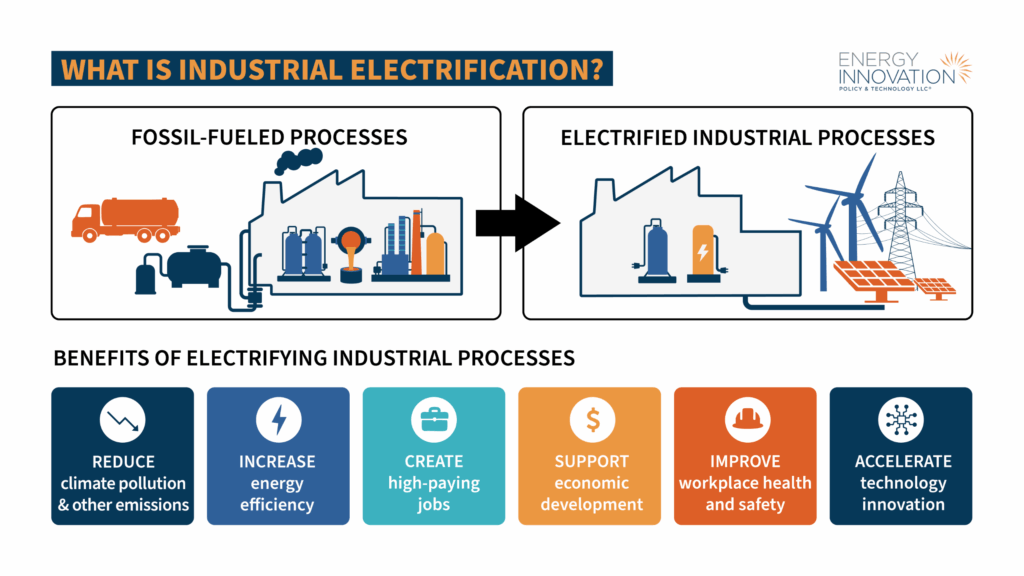

Direct electrification (backed by clean electricity) is usually the best approach to supplying energy to industrial processes while cutting pollutant emissions. Direct electrification has benefits for society, including reductions in climate and conventional pollutants, creating high-paying jobs, and accelerating technology innovation.

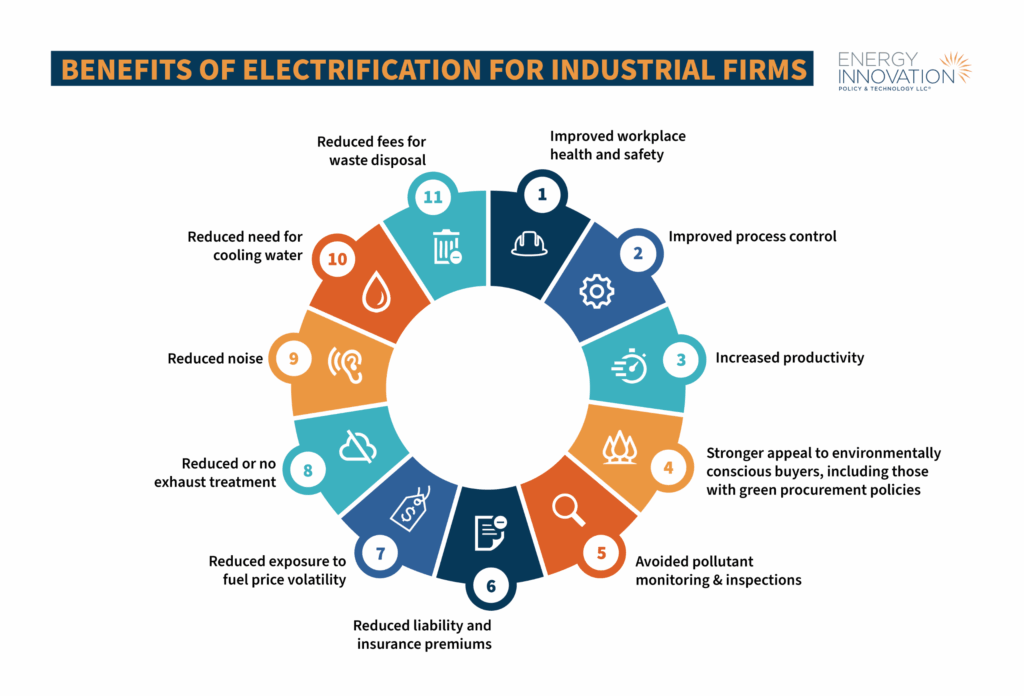

Electrification also provides numerous benefits to industrial firms, such as improved workplace health and safety, improved process control, increased productivity, reduced or no exhaust treatment, reduced need for cooling water, and an improved ability to market products to environmentally conscious buyers, including companies and governments with green procurement policies.

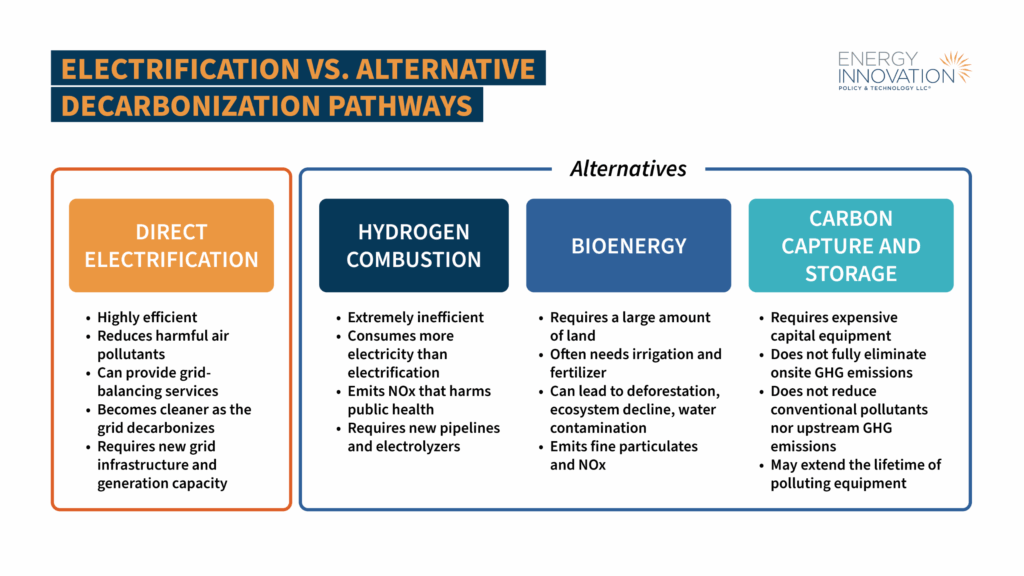

Alternatives to direct electrification that aim to avoid climate pollution – such as combustion of clean hydrogen, bioenergy, or fossil fuels with carbon capture and storage – have their own downsides.

Electrified technologies can deliver heat at all temperature ranges demanded by industry.

However, there are challenges to greater deployment of electrified industrial technologies. The largest challenge is the cost of electricity relative to the cost of natural gas and coal.

Electrification may entail a particularly high operating cost premium for industries that obtain energy by burning the byproducts that they create on site. Industries that rely heavily on byproduct fuels—the refining industry, the pulp and paper industry, and the wood and wood products industry—collectively account for around 10 percent of the global industrial sector’s emissions and around 16 percent of the industrial sector’s on-site emissions from fuel combustion.

Fortunately, there are solutions. For example, low-temperature heat can be provided by industrial heat pumps. By moving heat instead of creating it, they can deliver several times more energy than the amount of electricity they consume. Their efficiency is highest when they deliver a smaller temperature increase.

Another solution involves deploying renewables, which produce inexpensive electricity that can drive down the market price in many hours of the day. Many regions of the U.S. with large shares of renewable generation (typically onshore wind in the center of the country, and high levels of solar and battery energy storage in much of Texas and southern California) have the lowest wholesale electricity prices. The wholesale price of electricity can be under $10/MWh ($2.78/GJ), which can be competitive with natural gas, particularly when considering that electricity provides industrial heat and services more efficiently than gas.

All relatively technologically mature opportunities to electrify non-feedstock energy use in the U.S. would shift 66 percent of non-feedstock fossil fuel demand to electricity. The required capital investment in industrial equipment would be around $289 billion, not including costs of installation or electricity capacity and grid upgrades.

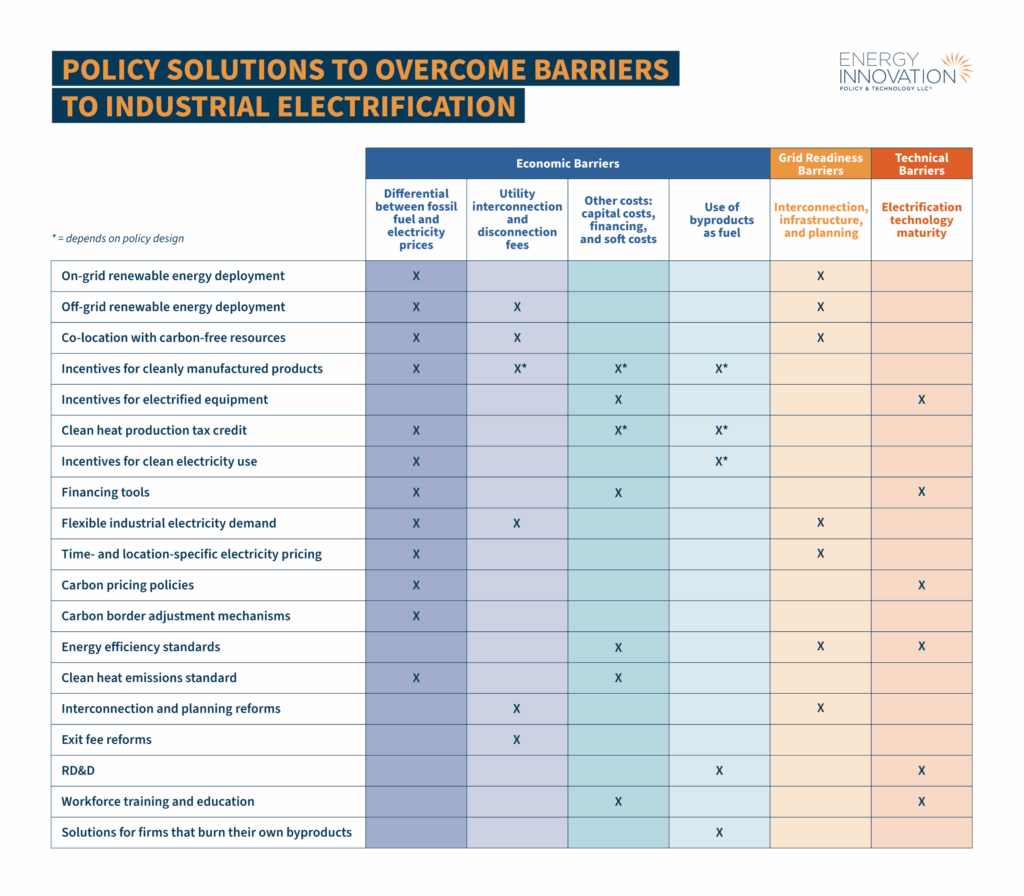

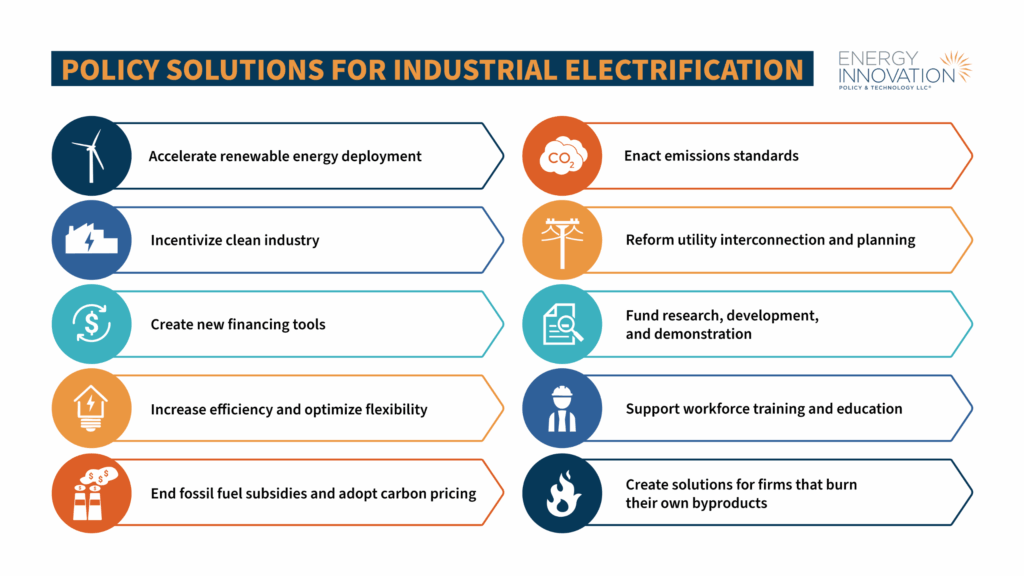

A range of policy solutions can promote industrial electrification.

A more detailed breakout shows how each policy can help address the main barriers to industrial electrification.